Introduction

Multi-tenant SaaS businesses with many products and microservices face unique challenges in version control. With separate customer deployments and the need to hotfix older service versions, choosing the right Git branching strategy is critical. A good branching model helps balance rapid continuous delivery with the ability to support multiple versions and tenant-specific configurations. In Azure DevOps Repos (Git) and Azure Pipelines, teams can adopt various strategies. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of GitFlow, trunk-based development, release branch strategies, and feature branching (GitHub Flow) in the context of Azure DevOps. We’ll examine how each approach impacts CI/CD pipelines, per-tenant deployments, backward compatibility, and legacy support, with examples and diagrams to guide development managers and teams.

Common Branching Strategies Overview

Before diving in, here’s a quick overview of the strategies we’ll compare:

- GitFlow: A classic model with multiple long-lived branches (e.g.

developandmaster) and support branches for features, releases, and hotfixes bmc.com. Suited for organized release cycles but can introduce complexity. - Trunk-Based Development: A lean approach where all developers integrate frequent changes into a single main (trunk) branch, using short-lived feature branches or even direct commits atlassian.com. Emphasizes continuous integration and feature flags over long-lived divergence.

- Release Branching: Maintaining dedicated branches for each release or version (e.g.

release/x.y) alongside the main branch learn.microsoft.com. New development happens in main (or a dev branch), while release branches stabilize and support specific versions with selective hotfixes. - Feature Branching (GitHub Flow): A lightweight workflow with one deployable main branch and short feature branches for each change bmc.com. Each feature branch is merged into main via pull request once approved, and main is kept always production-ready.

Each strategy has implications for how you set up Azure DevOps pipelines and manage deployments to many tenant environments. Let’s examine them one by one.

GitFlow Strategy

GitFlow is a well-known branching model that defines a strict separation of branches for different purposes. In GitFlow, the team maintains two primary branches: master (production-ready code) and develop (integration of ongoing development). From these, you create supporting branches for features, releases, and hotfixesbmc.com. This structure is illustrated below, with master and develop as long-lived branches and others as needed:

GitFlow uses two main branches (master and develop) and support branches for features, releases, and hotfixes. This model cleanly separates ongoing development from finished releases bmc.com.

How GitFlow Works: Developers branch off develop for each new feature (e.g. feature/xyz). Feature branches merge back into develop once the feature is complete. When it’s time for a release, a release branch is created from develop (e.g. release/1.2), where final fixes, version bumps, and QA happen nvie.com. The release branch is then merged into master (tagging a release version) and back into develop nvie.com. For urgent production bugs, a hotfix branch is spun off directly from master (the current live version), fixed, then merged into both master (deploying the fix) and develop bmc.com nvie.com. This ensures the hotfix goes out immediately and also enters the upcoming codebase.

Impact on CI/CD: GitFlow can integrate with CI/CD pipelines, but it adds complexity. Each branch type often corresponds to a pipeline or environment: for example, Azure Pipelines might build every commit on develop and deploy it to a staging environment, while merges into master trigger production deployments. You can set up branch-based pipeline triggers (e.g. only trigger the production release pipeline on changes to master). Because code on develop is not deployed to prod until merged to master, there’s an inherent gating – which can be good for quality control but slows down delivery. GitFlow’s long-lived branches mean changes might sit in develop for a while, so integration testing happens there rather than in prod. Azure DevOps supports this with features like branch policies (e.g. require PR reviews before merging to master or develop) and separate build pipelines per branch. However, one drawback noted is that GitFlow can be challenging to use with full continuous integration/continuous delivery (CI/CD) automation atlassian.com. The extra merge steps and branch synchronization (e.g. remembering to merge hotfixes into develop) can complicate pipeline scripts. Still, for teams that do scheduled releases, GitFlow provides clear checkpoints: you could have a CI build on each feature branch for unit tests, a QA/staging pipeline for the release branch, and a production pipeline for master.

Tenant-Level Deployments: In a multi-tenant SaaS, using GitFlow to manage per-tenant deployments is generally not recommended if each tenant is meant to run the same application version. You could theoretically maintain separate branches per tenant, but that quickly becomes unmanageable. (For example, having a “develop” and “master” for each customer would explode into dozens of branches.) Instead, tenants should ideally be kept on a common codebase, with configuration toggles to customize features per tenantstackoverflow.com. GitFlow excels more at managing multiple versions of the product (e.g. version 1.x vs 2.x) rather than multiple variant codebases for each tenant. If you do have different tenants on different release versions, GitFlow’s structure can handle it by letting you maintain older release branches. For instance, if some customers haven’t upgraded from v1.2 to v1.3, you might keep a release/1.2 branch alive for critical fixes while new development continues on develop (headed for v1.3). This way, you can hotfix the older version via a hotfix branch off the release/1.2 and merge it back into that branch (and into develop if applicable). GitFlow’s organized branching makes it possible to juggle multiple versions, but it’s a lot of overhead if dozens of tenants all require different versions – better to avoid that scenario when possible.

Backward Compatibility and Legacy Support: One advantage of GitFlow is that it cleanly supports parallel development on new features and maintenance of older releases. The dedicated release and hotfix branches mean you can apply a patch to an older version without immediately mixing it with ongoing feature development bmc.com. For example, a hotfix branch from master might address a production bug in version 2.0, while the develop branch is already working toward 2.1. GitFlow ensures the 2.0 fix can be merged into both places so nothing is forgotten. This strategy is ideal if you must maintain multiple production versions (enterprise customers on different schedules, on-premise editions, etc.) bmc.com. Each version can have its own branch history. However, the flip side is that the Git history can become complex and harder to read, and coordinating merges is labor-intensive bmc.com. You also risk divergence if the team forgets to port a fix from a hotfix branch into develop (causing a regression later). In practice, Azure DevOps teams often automate cherry-picking of commits between branches to reduce manual error – for instance, using Azure DevOps pipeline tasks or scripts to propagate hotfix commits to develop. Overall, GitFlow trades off speed for control: it’s great for structured releases and legacy support, but it slows down continuous deployment. In fact, GitFlow is generally not recommended when you aim to maintain a single live version with fast continuous delivery bmc.com atlassian.com, because the develop/master split and long-lived branches add friction.

Pros and Cons Summary: GitFlow provides a very organized approach: clear separation of stable vs. in-progress code, and the ability to support multiple release lines. This can instill discipline in a team and align with formal release management processes (e.g. QA on a release branch, then prod) bmc.com. It’s supported by many tools and familiar to many developers. On the downside, it can over-complicate your workflow for a SaaS that is continuously deploying a single product version bmc.com. Merging and maintaining two main branches (plus many sub-branches) adds overhead. In Azure DevOps, you might find yourself with redundant build pipelines or extra steps to merge and deploy. Thus, many SaaS teams have moved toward simpler models once high-frequency deployment and feature-flag techniques became common atlassian.com.

Trunk-Based Development

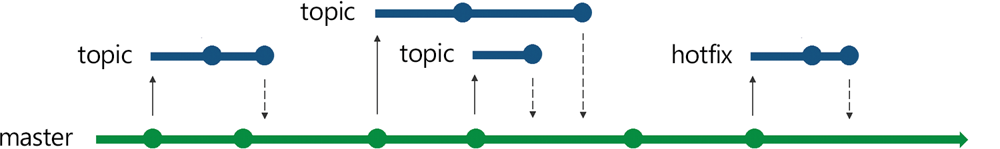

Trunk-based development (TBD) is a modern branching strategy that emphasizes a single integration branch (often the main branch, analogous to master) where all developers merge their work in small, frequent increments atlassian.com. In trunk-based workflow, long-lived branches are avoided. Developers either commit straight to the trunk or use short-lived topic branches for each feature/bugfix, which are merged into the trunk at least once a day or as quickly as possible bmc.com. The trunk (main) is always kept in a releasable state – in other words, it should always be stable enough to deploy atlassian.com.

Trunk-based development with short-lived “topic” branches. Here the green line is the shared trunk (main branch) and blue lines are brief feature or hotfix branches that merge back quickly. This continuous merging keeps the trunk always up-to-date and deployable atlassian.com.

How Trunk-Based Dev Works: All work converges to the trunk. If using branches, they are typically one per task, and exist only for a short period (often just hours or a couple of days of work). Teams practicing trunk-based development will integrate and push code to the main branch frequently, sometimes multiple times a day, to avoid large divergence atlassian.com. This requires strong discipline in writing incremental changes. Code in trunk is often controlled by feature flags or toggles such that incomplete features can be merged but toggled off until they’re ready for release. Martin Fowler describes this as “feature toggles + branch by abstraction” to avoid long-lived branches stackoverflow.com. In Azure DevOps, you would still likely create a feature branch for each work item (to facilitate pull requests for code review), but the key is that these branches are very ephemeral. Once the PR is approved and merged to main, the feature branch is deleted. Developers regularly pull the latest main to reduce merge conflicts. Automated tests (unit, integration) run on each commit to main to catch issues early. Essentially, trunk-based development embraces continuous integration – merging small changes continuously so that integration is a non-event atlassian.com.

Impact on CI/CD: Trunk-based development is highly CI/CD-friendly. Because the main branch is always kept deployable, you can hook your Azure Pipeline to automatically build, test, and even deploy each commit on main. Many teams using trunk-based development practice continuous deployment – every commit that passes tests can be deployed to production (perhaps behind feature flags if it’s not fully live). Even if you don’t auto-deploy every commit, the pipeline is simpler: you typically have one primary build/release pipeline tracking the main branch. In Azure Pipelines YAML, you might set trigger: branches: include: ['main'] to run on main. Pull request builds can still run on feature branches (using PR triggers) for validation, but those branches usually don’t have separate deployment stages. This simplicity is a big reason trunk-based development is considered a best practice for DevOps teams atlassian.com. By keeping merges small and frequent, integration conflicts are minimized and resolved early, which maintains a healthy, fast pipeline. Automated tests must be robust and run quickly, because main will be changed often – many trunk-based teams invest in high-speed tests and even parallel pipelines to keep up. One thing to plan in Azure DevOps is branch policies on main that require PRs to pass certain checks (like build and tests) before merging. This ensures the trunk stays green. Another consideration: with rapid merges, you might not deploy each commit separately if you have a regulated environment, but perhaps batch them – trunk-based dev doesn’t dictate deployment frequency, just integration frequency. You could, for example, deploy the accumulated trunk changes at the end of each day or sprint. The Azure DevOps team itself follows a trunk-based approach but only deploys to production at the end of a sprint (3 weeks), as a way to balance speed and stability devblogs.microsoft.com.

Tenant-Level Deployments: For multi-tenant SaaS, trunk-based development aligns well if all tenants use the same version of the product. The idea is to keep one live version (the trunk head, or something very close to it) and deploy it to all customers (perhaps gradually). Feature flags play a big role here. Instead of maintaining separate branches for each tenant’s custom needs, you include all variations in the trunk codebase behind configuration switches. For example, if Tenant A and Tenant B have different features enabled, the code for both features lives in main, but toggles determine who sees what stackoverflow.com. This approach prevents code divergence and eliminates “merge hell” caused by branching per tenant. As one Stack Overflow discussion noted, trying to use version control branches to manage per-tenant feature differences becomes “a huge mess” of diverging versions and duplicated fixes, whereas a single configurable codebase is far easier to maintain stackoverflow.com. In practice, you might deploy the same main build to all tenant environments but with different config files or database settings per tenant to turn features on/off. Azure Pipelines can facilitate this by deploying the same artifact to multiple App Services or containers, each configured for a tenant. If you have many tenants, you might use a script or multi-release pipeline to loop through tenants. The key is that they’re all running code from the main trunk, which simplifies testing and ensures that hotfixes apply to everyone uniformly. Backward compatibility must be considered within the code (e.g. if a database schema changes, it might need to be backwards compatible or behind a feature flag until all tenants are migrated).

Backward Compatibility and Legacy Support: Pure trunk-based development assumes you are essentially not maintaining old versions – you are continuously pushing forward. There typically are no long-lived “old version” branches; the main branch moves forward and all customers eventually get the new code. This means you design changes to be backward compatible where possible, or use techniques like blue-green deployments and feature flags to roll out changes safely. If a critical bug is found in production, you fix it on the main branch immediately (since that’s what’s deployed, or about to be deployed) and redeploy. But what if you must support an older version that some tenants are still using? In trunk-based mentality, you’d likely handle that by quickly upgrading those tenants rather than keeping a separate code line. If a separate code line is unavoidable (say a certain customer is on an on-premise older release), you would then have to create a branch off the historical commit for that release – effectively treating it like a one-off release branch. For example, if version 1.0 was tagged months ago, you can branch from the 1.0 tag, apply a fix, and deploy that as 1.0.1 to that customer, then merge that fix back into trunk (if relevant) devblogs.microsoft.com. Trunk-based teams try to minimize this by moving everyone to latest, but the option exists to branch as-needed. Notably, the Azure DevOps (formerly VSTS) team practices an approach called “Release Flow” which is basically trunk-based development with cherry-picked hotfixes for the current release. They commit all changes to master first, and if a hotfix is needed in production, they cherry-pick that commit into the deployed release branch devblogs.microsoft.com. The philosophy is “main first”: never fix something only in an old branch – fix it in main then port it, to avoid regression devblogs.microsoft.com. In trunk-based workflows, backward compatibility is ensured by continuous integration: since everyone’s merging often, issues surface quickly and the code in main tends to be more stable overall (no big bang merges). This yields higher software delivery performance atlassian.comatlassian.com. The main caution is that trunk-based development relies heavily on feature flag discipline – improperly managed feature toggles can create complexity or technical debt in the codebase if old flags aren’t cleaned up bmc.com. Also, adopting trunk-based dev can be a culture shift if a team is used to GitFlow; training and gradual adoption may be needed bmc.com.

Pros and Cons Summary: Trunk-based development offers rapid integration, simpler workflows, and is ideal for true CI/CD where you deploy often. The main branch is always shippable, so releases can be done at will. It reduces merge conflicts and encourages modular, incremental code changes atlassian.com. For a multi-product microservices SaaS, trunk-based development can dramatically speed up development across teams, since each service’s trunk can flow to production independently with minimal ceremony. The downsides include the need for robust testing and feature flag systems (to avoid releasing incomplete features inadvertently) and the fact that it doesn’t inherently provide a method to maintain multiple prod versions – you have to create temporary branches if needed, which Release Flow addresses. Some developers also find it hard to break the habit of long feature branches and may initially struggle with the “commit early, commit often” style; it requires strong DevOps culture and tooling. In summary, trunk-based development is recommended for fast-moving SaaS teams that deploy frequently and have the majority of tenants on the latest version. It’s considered a modern best practice by many (Google’s DORA metrics and others tie high deploy frequency to trunk-based workflows) atlassian.com, and Azure DevOps itself encourages a simplified branch strategy built on a stable main branch learn.microsoft.com.

Release Branching Strategy (Release Flow)

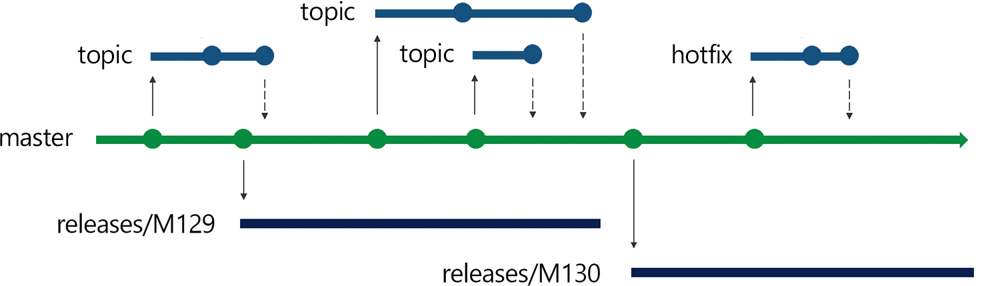

The “release branch” strategy can be seen as a hybrid approach. It involves creating a branch for each release or maintenance version, allowing isolation of that code after it’s cut, while new development continues elsewhere. Unlike full GitFlow, you might not have a permanent develop branch – often teams practicing this have a single main/trunk where active development happens, and when a release is due, they create a branch off main to stabilize and eventually deploy that release. This branching model is used by many SaaS teams that do batch releases and need to support hotfixes on the current or past release. Microsoft’s Azure DevOps team dubbed their flavor of this strategy “Release Flow” devblogs.microsoft.com.

How Release Branching Works: In this strategy, main (or develop) is the stream of ongoing work, and at a release milestone, a release branch is created. For example, at the end of sprint 10 you branch releases/v10 from main. That branch is deployed to production for sprint 10’s release, while the main branch now gears up for sprint 11 work devblogs.microsoft.com. The release branch might receive some final testing, bug fixes, or configuration changes (like bumping a version number, updating release notes, etc.). Crucially, once the release is deployed, you keep that branch around at least until the release is fully live and stable. If an urgent bug is found in production, you can fix it on the release branch and redeploy quickly without pulling in other in-progress features from main. Typically, you would also merge that fix back into main (or vice versa, do it in main and cherry-pick to the release branch) devblogs.microsoft.com. Over time, you might accumulate multiple release branches if you support multiple versions (e.g. releases/2.0, releases/1.9 for a previous version still under support). However, many SaaS teams only keep one active release branch at a time – basically maintaining a branch for the currently deployed version, and perhaps the immediate previous version if rolling deployments. Once no servers (or tenants) are running the old release, that branch can be retired or kept only for history devblogs.microsoft.com.

Release Flow in action: the main trunk (green) produces regular release branches (blue) like releases/M129 and releases/M130 for each sprint. New feature “topic” branches continue off main for future work, while the release branch isolates the code that’s actually in production. Hotfixes (blue branch labeled “hotfix”) can be applied to production code and then merged or cherry-picked back into main devblogs.microsoft.com.

In Azure DevOps terms, this strategy means at release time you create a branch in the repo (Azure Repos Git) with a clear name like release/20.09 or release/1.2. That branch might trigger a specific Release pipeline that deploys to production. Meanwhile, your build pipeline for main continues building new commits for the next version, but those aren’t deployed until you cut the next branch. Microsoft’s VSTS team, for instance, names release branches by sprint number (as in the figure above: releases/M129, M130, etc.), deploys that branch, and when the next release comes they simply branch again from the updated main devblogs.microsoft.com. They even delete the old release branches after the deploy is fully rolled out devblogs.microsoft.com (to avoid clutter), focusing only on the current production branch and main.

Impact on CI/CD: The release branch strategy can be viewed as “trunk-based development with a safety net.” During normal development, teams merge into main often (like trunk-based), possibly deploying to a test environment continuously. But production deployments happen from a designated release branch, not directly from main. This affects your CI/CD setup: you will have multiple integration points. For example, you might have: (1) a continuous integration pipeline on main that runs builds and unit tests for every commit (and maybe deploys to a QA environment), and (2) a separate pipeline that triggers when a release branch is created or updated, which runs a full release build, then deploys to staging and production. Azure Pipelines supports branch conditions and triggers so you can have one YAML pipeline with conditional stages (deploy stage runs only on the release/* branches), or separate pipelines for dev vs release branches. A benefit here is that the release branch can have a slower, more robust pipeline (including manual approvals, longer-running tests, etc.), while main can have a faster feedback cycle pipeline. Also, by having a stable release branch, you avoid the “deployment queue” problem of trunk-based where multiple PRs might contend to deploy at once devblogs.microsoft.com. Instead, you batch changes into the release branch and deploy them together, which can be easier to coordinate for large teams or multiple microservices that need to align.

Tenant-Level Deployments: If each tenant runs the exact same code version, then release branches simply represent the version that all tenants are on. In that case, this strategy is similar to trunk-based for tenants (everyone is updated to the new release eventually), just with a controlled rollout. However, if tenants have staggered upgrades – say some tenants choose to stay on last quarter’s release while others move ahead – then you will indeed have to maintain multiple release branches in parallel. One tenant’s environment might be pointed at the release/2023Q4 branch while another is on release/2024Q1. This scenario often arises in B2B SaaS where customers have change management processes. The release branch model can handle it: you’d backport critical fixes to the older branch as needed. For instance, a security fix might need to be applied to both release/2024Q1 (current) and release/2023Q4 (for the customer who hasn’t upgraded). In Azure DevOps, you could even tie separate pipeline stages or variables to deploy to specific tenant environments from the corresponding branch. It’s doable, but it increases complexity – effectively you are managing multiple product versions. The strong guidance from DevOps experts is to minimize how long and how many old release branches you keep around. Feature flags and configuration can again help here. Ideally, even if you have separate release branches, the differences between them are small (mostly just lacking the latest features). If tenant-specific customization is needed, prefer implementing it via toggles rather than forked code. Release branches should primarily exist for timing differences (one tenant gets the code later), not for permanent code differences.

Backward Compatibility and Legacy Support: The release branching strategy is inherently designed to support legacy versions, at least for the short-to-medium term. Because you can carry a branch for an older release, you can apply patches on that branch without merging all new features. This means you don’t have to force all customers to update in lockstep. It is, in effect, the way to have multiple supported versions using Git without full GitFlow overhead. However, note that this is essentially what GitFlow also does with its support branches – the difference here is scale. In release branching, you might only maintain, say, the last one or two releases, whereas classic GitFlow in a product company might maintain many (the model is the same, though). For backward compatibility, teams often follow the rule that all fixes go into main first, then are cherry-picked into release branches as needed learn.microsoft.com devblogs.microsoft.com. This is the “master-first” approach the Azure DevOps team uses to ensure no fix is lost devblogs.microsoft.com. It does mean that sometimes a bug that only exists in an older release (because main has diverged or refactored that area) might not need to go into main – that’s the rare exception when a PR can go straight to the release branch devblogs.microsoft.com. In Azure DevOps, the UI even provides a Cherry-Pick button on completed PRs to facilitate this workflow devblogs.microsoft.com. From a process perspective, you’ll want to document which releases are under support and have an easy way to propagate fixes between branches (git cherry-pick, or merging release->main or main->release carefully). Backward compatibility in the code is slightly less strained than in pure trunk-based, because if a change is not backward compatible, you can hold it in main until ready and not merge it into the current release branch. For example, you might be building a breaking API change for v2.0 in main while still patching v1.x on a release branch – you don’t have to make the v2.0 code compatible with v1, because v1 is running from a different branch. This can give developers more freedom to refactor in main. The cost is the extra merge/cherry-pick work. Overall, release branching provides a nice balance: you get much of the continuous integration benefits of trunk (developers primarily work on one branch, main), but you also have a controlled stream for production, and you can handle hotfixes methodically. It’s no surprise many SaaS teams use a variant of this (sometimes calling it “Partial GitFlow” or just “branching by release”).

Pros and Cons Summary: The release branch strategy (or Release Flow) works well for SaaS teams that deploy on a schedule (e.g. end of sprint) and want isolation of deployed code. Pros: It supports zero-downtime releases (you can deploy from the release branch while main is already moving to next features), and makes it easy to apply hotfixes to the live code without waiting for all new code to be ready devblogs.microsoft.com. It’s simpler than full GitFlow because you typically don’t have a persistent develop branch – main is your integration branch. Teams have reported that this strategy scales to large teams; for example, Microsoft with hundreds of developers uses sprint-based release branches to manage contention and keep velocity high devblogs.microsoft.com. Cons: There is still overhead in managing branches and cherry-picking fixes. If not managed well, you could forget to port a fix to main or vice versa (though policies and templates can mitigate this). Also, if you maintain too many release branches for too long, it can start to resemble GitFlow with its complexity. Another con is that feature work may effectively be “blocked” from prod until the next release branch is cut – if your main has a feature finished right after a release, that code might not go live until the next release cycle. This delay is why truly continuous deployment teams prefer trunk-based with no separate release branch. But for many SaaS orgs, a short delay (maybe every 2 weeks) is acceptable for the trade-off of stability. In summary, release branching is often the best choice when you need both speed and control – it’s developer-friendly (work on main freely) and manager-friendly (production is protected on its own branch).

Feature Branching (GitHub Flow)

Feature branching – often exemplified by GitHub Flow – is a simpler workflow where the main branch is the only long-lived branch, and every feature or fix is developed in a short branch that is merged into main when readybmc.com. In practice, feature branching overlaps with trunk-based development, since both encourage using branches for changes and merging to one main line frequently. The distinction is sometimes in how long features live and how releases are handled. GitHub Flow assumes a continuously deployable main: “Anything in the master branch is deployable.”bmc.com. Developers create a branch off master (named after the feature or issue), commit work to that branch, then open a pull request. After review and CI checks, the branch is merged into master and deployed. There are no separate dev or release branches; it’s a streamlined process:

- Main branch – always stable, deployable state (often deployed immediately after merges).

- Feature branches – created from main for each change, and merged back into main via PR when done bmc.com.

- No dedicated release or hotfix branches in steady-state – if an urgent fix is needed, you create a branch for it from main, then merge back (which is essentially the same as a short-lived feature branch workflow).

GitHub Flow is essentially a subset of trunk-based development (with perhaps slightly less emphasis on daily merges – a feature branch might span a couple days or a week in GitHub Flow, though shorter is better). It works best when deployments are frequent. Many cloud-native projects and small teams use this because it’s very simple to understand.

Impact on CI/CD: Feature branching as per GitHub Flow is very CI/CD-centric. You will typically have an automated pipeline that triggers on pull requests to run tests (to ensure the branch won’t break main), and another trigger on merges to main to deploy the new changes. In Azure DevOps, implementing GitHub Flow is straightforward: you set up one primary pipeline for the repo’s main branch. Every PR could trigger a build validation (via branch policies and Azure Pipelines integration). Once merged, that pipeline (or a release stage) deploys the changes to production. Because there are no stage gates like a “develop” branch or a “release” branch, the time from code complete to code in production can be very short – potentially minutes, if your tests pass. This strategy naturally pairs with techniques like continuous deployment and can achieve very high deployment frequency (multiple times per day). However, as noted earlier, at massive scale (hundreds of devs, dozens of merges daily) you might hit coordination issues – e.g. if your process requires that every PR be deployed to a test slot before merging, you get a queue of deployments. GitHub Flow doesn’t prescribe deploying each PR independently, but GitHub’s own culture encourages testing in production or in realistic environments. Azure DevOps allows flexibility here: you might merge PRs freely and have a nightly build to deploy all new changes together, which is still GitHub Flow in branch structure (only main + feature branches) but not deploying every single merge. The CI pipeline in this model tends to be simpler than GitFlow’s because you only worry about one mainline; there is no need to merge between branches. One thing to consider is using tagging or releases in Azure DevOps to mark deployments – since you don’t have a release branch, you might use Git tags or the pipeline’s release artifacts to identify versions for rollback or audit. The Microsoft Learn guidance notes that some workflows use only tags to mark releases, but that introduces extra manual steps, whereas using a branch can be more explicit learn.microsoft.com. With GitHub Flow, you rely on tagging if you need to mark a production version, or you just rely on the commit history of main.

Tenant-Level Deployments: In a pure feature branch (GitHub Flow) model, all tenants get the same main branch code. So it assumes a unified SaaS deployment for all customers – usually the case in multi-tenant systems. If you need to deploy features to one tenant and not another, you again resort to feature flags rather than branching. For example, you might merge a feature toggled “off” by default, and only enable it (via config or a database flag) for a beta customer initially. This way, the code lives in main but doesn’t affect other tenants until turned on. That approach fits nicely with GitHub Flow because you maintain the simplicity of one branch. If a particular tenant is on a lagging schedule and can’t take new deployments for a while, technically you would have to pause updates for them (maybe run an older build of main) – but that’s essentially not following GitHub Flow at that point, since you’ve diverged. A true GitHub Flow assumes you don’t have permanent divergence; all live deployments track the main branch. So, in multi-tenant SaaS, you typically couple GitHub Flow with the policy that “all tenants are always on the latest version” (or very close to it). If that’s too strict, that’s when you lean towards release branches. In summary, feature branching is fine for multi-tenant SaaS when you treat it as one global service. Many web startups do exactly this – every user (tenant) sees the same app version, continuously updated. Enterprise SaaS with separate customer instances might have to modify it or move to a release branch model when needed.

Backward Compatibility and Legacy Support: Feature branching (with a single main) doesn’t provide inherent support for old versions. There is no concept of maintaining an older code line; you’re always pushing forward. If a critical issue arises in production, you branch off main, fix it, and merge back – if main has moved on with other changes that aren’t ready to deploy, this could be tricky. Ideally, main only contains tested, ready code (with toggles for anything unfinished), so deploying it is fine. One could also temporarily create a branch from an earlier commit (the last good deploy) to apply a quick fix and deploy that, but then you’d merge that fix into main as well. This is essentially equivalent to a hotfix in GitFlow, just without the formal structure. The lack of formal release branches means you have to be confident in the stability of main and your ability to quickly revert or turn off problem features. Backward compatibility issues (like removing or changing APIs) need careful handling: you might need to deploy supporting code first, or use toggles, because you can’t keep an older API version on a separate branch easily – you’d instead keep the old API code in main until clients migrate, and maybe mark it deprecated. In microservices, you’d deploy new versions that handle both old and new contract until all callers are on the new version. Essentially, you bake compatibility into the software, not the source control. This demands good deprecation policies and communication with any external consumers of your APIs.

Pros and Cons Summary: Feature branching/GitHub Flow is extremely simple and works great for small teams or services where continuous delivery is the goal. Pros: Very low overhead – only one main branch to maintain, everything else is short-lived. It’s easy for developers to understand (branch, commit, PR, merge, done) and there’s less merge debt since you integrate as soon as the feature is ready. It encourages automation and quick releases. Cons: It assumes a high level of automated testing and feature toggle maturity, because you don’t have a sheltered “develop” or “release” phase – code goes straight to prod from PR merge, so any deficiencies in testing can directly impact production. It also doesn’t handle multiple active versions well; if you need to support a long-term older version, you have to break the flow and create a branch for it (which basically shifts you to a release branch strategy). Coordination in very large teams can become an issue as mentioned; many large projects modified GitHub Flow by introducing a release branch or by batching deployments to avoid contention. In Azure DevOps, implementing GitHub Flow is arguably the easiest: you create repo, everyone works on branches and merges to main, and one pipeline handles it all. It’s a good starting strategy – as complexity grows, you can introduce release branches or other controls as needed.

Comparison and Recommendations for SaaS Scenarios

Choosing a branching strategy in a multi-product SaaS environment should be guided by how often you release, how many versions you need to support, team size, and tenant requirements. Below is a comparison of the strategies across key considerations:

- Speed of Delivery (CI/CD): Trunk-based and Feature Branch (GitHub Flow) enable the fastest delivery. They are designed for continuous integration and can support deployments on demand atlassian.com. GitFlow is slower – changes accumulate in develop and only deploy when merged to master, which might be infrequent. Release Branching is intermediate: you can integrate continuously on main, but actual releases happen at intervals (e.g. end of sprint). For a SaaS aiming at multiple deploys per day, trunk-based or GitHub Flow is usually best. Azure DevOps and DORA research favour trunk-based for improving deployment frequency and lead time atlassian.com. If your organization has embraced DevOps and wants rapid iteration, lean towards trunk or GitHub Flow.

- Support for Multiple Concurrent Versions: This is where GitFlow and Release Branching shine. If you must maintain, say, a Version N and N-1 in production (perhaps some tenants on the previous version), having a branch for that older version makes it manageable. GitFlow explicitly allows many release and hotfix branches, but that can become heavy with too many versions. A lighter approach is to use release branches for the few versions you support and cherry-pick fixes bmc.com learn.microsoft.com. Trunk-based/GitHub Flow assume one version (no long-term parallel versions). So, if you promise clients support on an old release for X months, plan on using release branches or a GitFlow-like model. As a recommendation: try to minimize the number of versions and how long you support them. If possible, adopt a policy such as supporting N and N-1; anything older, force upgrade. This keeps the branching overhead reasonable. If customers demand freedom to stay far behind, you’ll lean more towards a GitFlow model, but note the productivity trade-off.

- Tenant-Specific Customization: Avoid branch-per-tenant strategies. Though it might be tempting to maintain separate branches for each tenant’s custom code, this becomes unsustainable (“a huge mess of diverging versions” as one expert put it)stackoverflow.com. Instead, use configuration files or feature flags that enable/disable modules per tenant at runtime. All strategies (GitFlow, trunk, etc.) can work with feature flags, but trunk-based and GitHub Flow practically require them for any differences. If you have a few large tenants with custom requirements that cannot be toggle-managed, one approach is to modularize the code (e.g. plugin architecture) rather than fork the codebase. If even that’s not possible, a compromise is to keep a separate branch for a heavily divergent customer but treat it as its own product (with its own cadence) – essentially a fork. That, however, is a last resort when the business case warrants a fork; it’s outside normal “branching strategy” and more a separate stream of development. Generally, one codebase for all tenants is a core principle of multi-tenancy; branching is not the right tool to segregate tenant behavior stackoverflow.com.

- Microservices and Multiple Products: Consider whether each microservice is in its own repository (likely in Azure Repos) – if so, you can choose a strategy per repo/service. Often, teams use trunk-based or GitHub Flow for microservices, because each service can be deployed independently and should remain small and easy to test. It’s common for microservice teams to adopt trunk-based development to keep high velocity (each service has one main, and maybe ephemeral support branches for hotfixes). If you have many products (different codebases), you don’t necessarily need the same branching strategy for all – but having a consistent approach across teams is beneficial for tooling and training. A large SaaS company might use Release Flow for their core monolith and trunk-based for newer microservices, for example. Azure DevOps pipelines can be standardized with templates to accommodate both scenarios. For instance, you could have a pipeline template parameterized by branch strategy: if “release branch” strategy, then include steps for cherry-picking or environment-specific triggers; if “trunk,” then always deploy latest.

- Team Size and Collaboration: Larger teams often need more structure to avoid chaos. GitFlow was historically popular for large teams because it clearly delineated where code goes and when it gets released. But many large organizations (including Microsoft) have shown that trunk-based with release branches scales well even to hundreds of devs devblogs.microsoft.com. The key is robust automation and communication. One potential strategy for a very large team is to use area branches or component branches temporarily – but this can backfire if it becomes siloed development. It’s usually better to use feature flags within trunk than maintain a long component branch. For moderately large teams, a good practice is to enforce short branch lifetimes and frequent merges (perhaps via sprint branch policies or automated reminders for stale branches). Azure DevOps can show metrics for PR cycle time which encourage trunk-based habits. If you find a feature will take a long time (e.g. a month of work), consider breaking it into incremental PRs or use a feature flag to merge partial work frequently (the “Branch by Abstraction” technique driftboatdave.com).

- Tool Support in Azure DevOps: All these strategies can be implemented in Azure DevOps, but some specific tips:

- Use branch policies: e.g. require PR for merges to main/master (this is useful in all strategies except perhaps a solo dev trunk scenario). For GitFlow, have policies on both develop and master.

- Use status checks and build validation on PRs to ensure merges don’t break the build learn.microsoft.com.

- Set up multiple pipelines or a single multi-stage pipeline with branch filters. For GitFlow or Release branches, you might have triggers like: if branch starts with

release/or ismaster, then deploy to Prod; if branch isdevelop, deploy to a test environment; if PR to develop, just build. Azure Pipelines YAML can usecondition:on stages to achieve this. - Tags vs Branches: The Microsoft guidance suggests using branches for releases rather than just tags, because branches are harder to forget and can receive commits (tags are read-only markers) learn.microsoft.com. So even if you do GitHub Flow, if you need to cut a stable release, it might be worth branching it. Conversely, if you do trunk-based CD, you might tag each prod deployment commit for reference. Use whatever helps you trace what’s running in production easily.

- Cherry-pick and Merge tools: Azure DevOps’s web interface supports cherry-picking a commit or a PR to another branch with one click devblogs.microsoft.com. This is extremely handy for Release Flow workflows. Encourage the team to use this instead of manually merging, to reduce mistakes.

- Visualization: Sometimes managers like to see a diagram of the branching strategy (like the ones in this guide). You can use tools or even Azure DevOps wiki to document your branch workflow. This sets expectations (e.g. “a hotfix must be done on master first, then cherry-picked to release branch” as a rule devblogs.microsoft.com).

Recommendations: For most modern SaaS teams, a trunk-based or release branch strategy will yield the best results. GitHub Flow (feature branching to main) is essentially a lightweight trunk-based approach and works well if you deploy continuously and don’t need to maintain old versions. Trunk-based with ephemeral release branches (Release Flow) is a great fit when you do iterative development but want a controlled release cadence and the ability to patch production quickly – this is arguably ideal for multi-tenant SaaS where all tenants get the update, but you release in stages (perhaps using deployment rings) devblogs.microsoft.com devblogs.microsoft.com. GitFlow, with its multiple long-lived branches, might still be useful if your organization has strict separation of environments or very long-lived versions (e.g. a SaaS that also ships an on-premise edition once a year might use a GitFlow model internally). But be aware that GitFlow can slow down your CI/CD and has largely been superseded by simpler flows in many companies atlassian.com.

If you are unsure, one strategy is to start simple (GitHub Flow) and introduce more branches as needed. For instance, begin with just main and feature branches. If you find you need a stabilizing period, introduce a release branch per version. If you further find you have multiple versions to juggle or a lot of hotfix traffic, then a develop branch might emerge (which starts to resemble GitFlow). Keep evaluating the pain points: are developers frequently waiting to integrate code (maybe too many long features – lean towards trunk integration)? Are ops/support asking for patches on last month’s release (need release branches)? By aligning branch strategy with deployment strategy, you ensure that your branching model aids rather than hinders your delivery.

Finally, no matter which branching strategy you choose, foster good engineering practices: merge frequently, write automated tests, and use feature flags for incomplete features or per-tenant variations. These practices will mitigate the downsides of any branching model. For a multi-tenant SaaS, having a single source of truth (branch) for the code and deploying configs for tenant differences is far simpler than having multiple code bases. As one Stack Overflow answer succinctly advised: “Stick with a single application, but make it configurable.” stackoverflow.com. The branching strategy then primarily deals with how to deliver changes to that single application in a reliable, manageable way. Choose the model that lets your team ship features with confidence and respond to bugs quickly, with the least overhead necessary.

Conclusion

Managing Git branches in Azure DevOps for a complex SaaS product is about finding the right balance between agility and control. GitFlow offers control and clarity at the expense of speed, trunk-based development offers extreme agility but requires discipline and robust DevOps practices, release branching gives a middle ground that many find practical, and simple feature branching (GitHub Flow) keeps things lightweight and works well with modern CI/CD. In 2025’s fast-paced DevOps culture, many organizations have gravitated away from the heavy GitFlow model toward approaches that keep the main branch “always shippable” atlassian.com use branches only for short-term work isolation. Azure DevOps is flexible enough to support any model, but the tooling and guidance from Microsoft tends to encourage a simpler branch strategy with a high-quality main branch learn.microsoft.com.

For a multi-tenant SaaS with many microservices, our conclusive recommendation is to adopt a trunk-based or Release Flow strategy. Use feature flags for tenant-specific needs instead of branching, and introduce release branches when you need to maintain an older version or coordinate a staged rollout. Reserve GitFlow’s full complexity only for cases where you truly have many concurrent versions to support and a slower release cadence that justifies it. By doing so, you empower your developers to deliver value continuously and your operations to handle deployments and hotfixes gracefully. The ultimate goal is a branching strategy that is developer-friendly (easy to collaborate and merge code) and manager-friendly (supports the business’s release and support commitments). The strategies and examples in this guide should equip you to implement the approach that best fits your SaaS scenario, and Azure DevOps will be the backbone to automate and enforce your chosen workflow. Happy branching and shipping!

Sources:

- Atlassian Git Tutorial – “Gitflow has numerous, longer-lived branches and larger commits… challenging to use with CI/CD.” atlassian.com

- BMC Software DevOps Blog – Advantages/Disadvantages of GitFlow (multiple versions, complexity) bmc.com

- Microsoft DevOps Blog (Edward Thomson) – Release Flow on the VSTS Team (sprint branches, cherry-picks) devblogs.microsoft.com

- Microsoft Learn – Azure DevOps team’s branch strategy and cherry-pick guidance learn.microsoft.com devblogs.microsoft.com

- Stack Overflow – Feature flags vs branches for multi-tenant features (Elliot Blackburn’s advice) stackoverflow.com

- Atlassian – Trunk-based development definition and benefits for CI/CD atlassian.com

- Microsoft Learn – “How Microsoft develops with DevOps” (trunk vs GitHub Flow, deploy queue issue) learn.microsoft.com devblogs.microsoft.com

- Azure DevOps Docs – Branching guidance (release branches vs tags, deployment branches) learn.microsoft.com

Leave a comment